- 6004 S REGAL ST, SPOKANE, WA 99223. MON-SAT 12–6PM TUE & SAT 11AM–12 PM for high risk customers Library Supervisor.

- Caitlin Moran Q&A with Alexandra Hemminsley – Moranthology. Highlights from event with Caitlin Moran discussing anything and everything to celebrate the release of her book, Moranthology in 2012. Caitlin was chatting to Alexandra Hemminsley.

Find information about and book an appointment with Dr. Caitlin Anne Moran, MD in Atlanta, GA. Specialties: Infectious Diseases. Healthconnection™ 404-778-7777. 117k Followers, 284 Following, 106 Posts - See Instagram photos and videos from Caitlin Moran (@mscaitlinmoran).

Caitlin Moran House

Caitlin Moran at the 2016 Hay Festival | |

| Born | 5 April 1975 (age 46) |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Journalist, author, broadcaster |

| Spouse(s) | (m.1999) |

| Children | 2 |

Catherine Elizabeth 'Caitlin' Moran (/ˈkætlɪnməˈræn/;[1] born 5 April 1975) is an English journalist, author, and broadcaster[2] at The Times, where she writes three columns a week: one for the Saturday Magazine, a TV review column, and the satirical Friday column 'Celebrity Watch'.

Moran is British Press Awards (BPA) Columnist of the Year for 2010, and both BPA Critic of the Year 2011 and Interviewer of the Year 2011.[3] In 2012, she was named Columnist of the Year by the London Press Club,[4] and Culture Commentator at the Comment Awards in 2013.[5]

Early life[edit]

Moran was born in Brighton, the eldest of eight children; she has four sisters and three brothers. Her father, who is Irish, was a 'psychedelic rock pioneer' drummer who 'did session work with many well-known bands in the Sixties'[6] later 'confined to the sofa by osteoarthritis'.[7] Moran lived in a three-bedroom council house in Wolverhampton with her parents and siblings, an experience she described as akin to The Hunger Games.[8]

Moran attended Springdale Junior School and was then educated at home from the age of 11, having attended Wolverhampton Girls' High School[6] for only three weeks.[9] She and her siblings received no proper formal education from their parents; the local council allowed them to do so, as they were 'the only hippies in Wolverhampton'.[8] The children frequently occupied their time with simple games, such as throwing mud at their house.[8] Moran describes her childhood as happy, but revealed she left home as soon as she was able to do so at the age of 18.[8]

Journalism and writing career[edit]

Moran was convinced throughout her teenage years that she would become a writer.[8] At the age of 13 in October 1988 she won a Dillons young readers' contest for an essay on Why I Like Books and was awarded £250 of book tokens. At the age of 15, she won The Observer's Young Reporter of the Year.[10] She began her career as a journalist for Melody Maker, the weekly music publication, at the age of 16.[11] Moran also wrote a novel called The Chronicles of Narmo at the age of 16, inspired by having been part of a home-schooled family.

In 1992, she launched her television career, hosting the Channel 4 music show Naked City,[12] which ran for two series and featured a number of then up-and-coming British bands such as Blur, Manic Street Preachers and the Boo Radleys. Johnny Vaughan co-presented with her on Naked City.

Moran's upbringing inspired her TV drama/comedy series, Raised by Wolves, which began airing in the UK on Channel 4 in December 2013.

In July 2012, Moran became a Fellow of the University of Aberystwyth.[13] In April 2014, she was named as one of Britain's most influential women in the BBC Woman's Hour power list 2014.[14]

Moran's semi-autobiographical novel, How to Build a Girl (2014), is set in Wolverhampton in the early 1990s. It is the first of a planned trilogy, to be followed by How to Be Famous, and concluding with How To Change The World.[15] Moran co-wrote the screenplay for the film adaptation of the same name alongside John Niven. She also served as an executive producer on the film, directed by Coky Giedroyc, and starring Beanie Feldstein, Alfie Allen, Paddy Considine and Sarah Solemani.[16]

Feminism[edit]

In 2011, Ebury Press published Moran's book How to Be a Woman in the UK, which details her early life including her views on feminism. As of July 2012, it had sold over 400,000 copies in 16 countries.[17]

Moran is a supporter of the Women's Equality Party.[18]

In March 2017, in an article she wrote for the Penguin publishing house, Moran suggested that young girls should not read books written by men at all, or 'at least' until they are 'older, and fully-formed, and battle-ready', singling out the books written by:

...the Great White Males. Faulkner, Chandler, Hemingway, Roth. The canonically brilliant. The men in them are brilliant, clever, awkward, compelling, complex – their stories drag you in, their voices are unstoppable. The dazzle and flair is undeniable.[19]

Moran claimed that by never reading books by men when she was younger made her, 'perhaps', happier in herself, more confident about writing the truth and less apt to run herself down for her appearance, weight, loudness and unusualness 'than many, many other women'.[19]

Twitter[edit]

In August 2013, she organised a 24-hour boycott of Twitter in protest against the organisation's perceived failure to deal adequately with offensive content posted, sometimes anonymously, on public figures' Twitter feeds.[20]

In 2014, her Twitter feed became a controversial addition to the list of English A-Level set texts.[21] In June 2014 the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism reported she was the most influential British journalist on Twitter.[22]

Personal life[edit]

In December 1999, Moran married The Times rock critic Peter Paphides in Coventry; they have two daughters, born in 2001 and 2003.[23]

Awards and honours[edit]

- 2015 Glamour Awards, Columnist of the Year

- 2013 Comment Awards, Culture Commentator of the Year

- 2012 London Press Club, Columnist of the Year

- 2012 Glamour Awards, Writer of the Year

- 2011 Galaxy National Book Awards, Book of the Year, How to Be A Woman

- 2011 Galaxy National Book Awards, Popular Non-Fiction Book of the Year, How to Be A Woman

- 2011 British Press Awards, Interviewer of the Year

- 2011 British Press Awards, Critic of the Year

- 2011 Irish Book Award, Listeners Choice category, How to Be A Woman

- 2011 Cosmopolitan, Ultimate Writer of the Year[24]

- 2010 British Press Awards, Columnist of the Year

Bibliography[edit]

- Moran, Caitlin (1992). The Chronicles of Narmo. Corgi. ISBN0-552-52724-6.

- Moran, Caitlin (2011). How to Be a Woman. Ebury Press. ISBN978-0-09-194073-7.

- Moran, Caitlin (2012). Moranthology. Ebury Press. ISBN978-0-09-194088-1.

- Moran, Caitlin (2014). How to Build a Girl. Ebury Press. ISBN978-0-09-194900-6.

- Moran, Caitlin (2016). Moranifesto. Ebury Press. ISBN978-0091949044.

- Moran, Caitlin (2018). How to be Famous. Harper. ISBN978-0062433770.

- Moran, Caitlin (2020). More Than a Woman. Harper. ISBN978-0062893710.

References[edit]

- ^'Caitlin Moran - How To Be a Woman'. Penguin Random House UK. 13 December 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- ^Rollman, Hans (12 November 2014). 'Caitlin Moran: Lady Sex Pirate and Working Class Hero'. PopMatters.

- ^'Press Awards 2011: Caitlin Moran's speech'. The Guardian. 6 April 2011.

- ^'BBC Newsnight journalists win award for spiked Jimmy Savile investigation'.

- ^'2013 Winners'. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. The Comment Awards

- ^ ab'INTERVIEW / Atrocious mess, precocious mind: Meet Caitlin Moran'. The Independent. 17 May 1994.

- ^Aida Edemariam 'The Saturday interview: Caitlin Moran', The Guardian, 18 June 2011.

- ^ abcdeBBC Radio 4: 'My Teenage Diary', First Broadcast 6:30PM Wed, 4 July 2012.

- ^The Times 2, p. 2. 28 December 2011.

- ^Moran, Caitlin (26 November 2007). 'My glorious career? I won it in a competition'. The Times. London. Retrieved 24 April 2009.

- ^'Pop on trial'. BBC Online. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^Davies, Huer (17 May 1994). 'Atrocious mess, precocious mind: Meet Caitlin Moran, newspaper columnist, television presenter, novelist, screenwriter, pop music pundit … and typical teenage slob'. The Independent. London.

- ^'Novelist and columnist honoured - Aberystwyth University'. www.aber.ac.uk.

- ^'Woman's Hour Power List 2014 – Game Changers'. BBC Radio 4.

- ^Caitlin Moran explores taboo subjects in her new book 'How to build a girl'. BBC Newsnight. 11 July 2014.

- ^Wiseman, Andreas (16 July 2018). 'Beanie Feldstein Comedy 'How To Build A Girl' Adds Cast, Lionsgate With Shoot Under Way'. Deadline Hollywood.

- ^Doll, Jen (16 July 2012). 'Caitlin Moran on How to Be a Woman, How to Be a Feminist'. The Atlantic Wire.

- ^Caitlin Moran (3 April 2016). Caitlin Moran@5x15 - Women's Equality Party (Video). 5x15 Stories via YouTube. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ^ ab'Ηow books made me a feministArchived 12 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine' by Caitlin Moran, Penguin website, March 2017

- ^'#TwitterSilence: Was Caitlin Moran's Twitter boycott an effective form of protest?'. The Independent. London. 5 August 2013.

- ^'English A-Level with Russell Brand and Dizzee Rascal on reading list under fire'. The Guardian. London. 6 May 2014.

- ^'Mainstream media 'still dominate online news''. BBC News: Technology. BBC. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^Moran, Caitlin (2011). How To Be a Woman. HarperCollins. pp. 275. ISBN9780062124296.

- ^'Cosmo's Ultimate Women of the Year Awards 2011 announced!'. Cosmopolitan UK. 4 November 2011. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013.

External links[edit]

- Portraits of Caitlin Moran at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Caitlin V Twitter

Christopher Hitchens once said that women just aren’t as funny as men and Caitlin Moran believed him. But that was many years ago — the great male essayist and orator has been dead for a decade — and Moran has matured into a bold, wise, middle-aged comedienne. When she was growing up in the 1980s, funny women such as Joan Rivers, Roseanne Barr and Victoria Wood ‘were rare and regarded as a freak of nature’. With retrospect, Moran realises that ‘Hitchens and I were, respectively, too male, or too young to have ever been invited into a coven — of which there are millions across the world’.

Moran’s new book is dedicated to her coven, also known as Team Tits. A coven is a place

If you are not currently a member of a coven, Moran hopes you will be soon, and in the meantime you can join hers.

Sex, of course, is a topic of interest within the coven: how can it be sustained inside a long-term relationship while cohabiting with young or teenage children? Moran describes scheduling ‘maintenance sex’ with her husband for the hour after the school bus has left. This led to ‘the Incident of 2009’, when one of her two daughters returned for a netball kit and heard the screamed injunction: ‘DON’T COME IN THE KITCHEN – WE’RE TRYING TO CATCH A RAT!’ Afterwards, ‘visual confirmation’ that the children were actually on the bus was required before ‘trouser time’.

Moran powerfully evokes the strains in a household where both parents are working:

In this situation, Moran explains, you really need to know that the guy in the truck coming towards you is

So do not marry or have children with a road-hog. Moran also strongly advises against becoming financially dependent on your partner: keep your career on the road if you possibly can, because one in three marriages ends in divorce, so ‘you’ll probably end up as a working mother anyway’.

More Than a Woman is a sequel to Moran’s feminist polemic How To Be a Woman, published to international acclaim ten years ago. In 2010, Moran believed she had done the hard part of growing up, sexually experimenting, finding love, securing work and starting a family; she thought the next decade would be easier, because teenagers sleep late, make their own breakfast and use the bathroom without parental supervision. She was heartbreakingly, devastatingly wrong. You do not need to have personally supported a child through an eating disorder or other forms of self-harming behaviour to value Moran’s life-affirming reports from the front line of absolute hell. Here she is describing the chronic (and shameful) crisis in child and adolescent mental health services throughout the UK:

Which means that if your child is not actually close to death, just dropping a kilogram of body weight a week, or slicing their arms in the bathroom, or too depressed to leave the house, or unable to stop washing their hands, you and your child must form an orderly queue and wait, perhaps a year or more, for help. ‘Why won’t they help me?’ Moran’s daughter sobbed at 2 a.m. ‘Help me. Help me. Help me. Help me.’ Words no parent in the deepest, darkest of nightmares ever wants to hear.

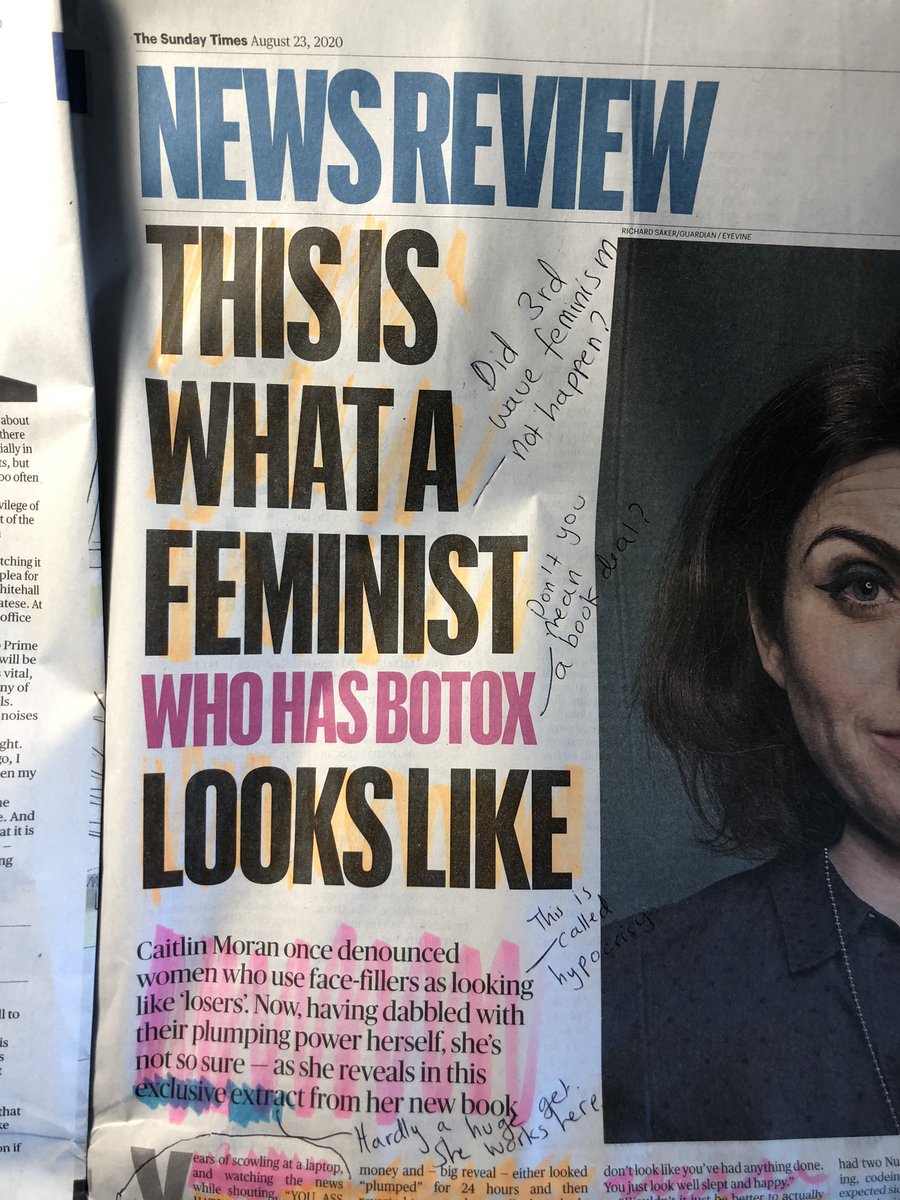

After three suicide attempts, Moran’s daughter made a full recovery. Emerging from years of crisis, Moran found herself in a period of peacefulness, feeling like a demobbed soldier or a former prime minister on a bus. From that place of calm and strength she revisits the question, what is feminism? She has no patience for ‘sisters eating sisters’ on hypervigilant social media. She is prepared to ask ‘What about the men?’ and to open the doors of her coven to them too. If men were more like women, more able to talk and support each other, that too would contribute to a better, more feminist world. Ultimately, Moran dreams of a worldwide Women’s Union: women will be cared for as they care for others, wear whatever they want, use botox if they choose to and save one another’s lives over and over again with peals of laughter, reassuring the next generation that being a woman is difficult, but also joyous, powerful and freeing.